On April 28, 2021, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case known as Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., which has been dubbed the “Cheerleader First Amendment Case.” This case raised several significant questions for the Court, including whether schools have the authority to regulate student speech that occurs outside of school grounds and, if so, what standard should be used to determine when off-campus speech can be regulated.

Case Background

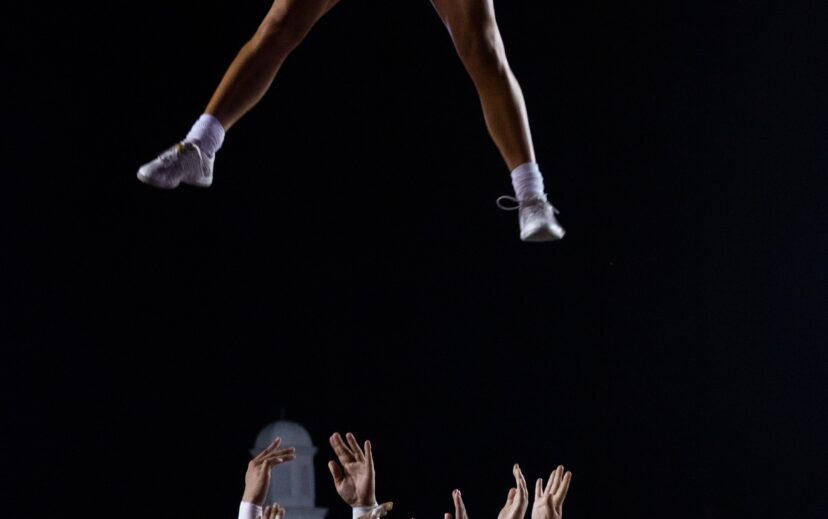

The case centered around a 14-year-old student, Brandi Levy or B.L., who was not selected for the varsity cheerleading team at her school. Upset by the decision, Levy posted a Snapchat story from a convenience store on a weekend, which showed her and a friend with raised middle fingers and a caption that read, “f*** school f*** softball f*** cheer f*** everything.” Although Snapchat stories are meant to disappear after 24 hours, a screenshot of Levy’s post was taken and shared with the school’s cheerleading coaches. They suspended her from the team for a year, citing a violation of a code of conduct policy that all cheerleaders, including Levy, were required to sign.

Ms. Levy sued the school, and the trial and appellate courts ruled in her favor. The school district appealed to the US Supreme Court, and the case was heard in April 2021.

The Tinker Decision

The central question in the case was whether schools have the authority to regulate student speech that occurs outside of school grounds. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a landmark Supreme Court case from 1969, the Court held that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” However, the Court also ruled that schools can regulate student speech that “would materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school” or invade the rights of others.

The Application of Tinker “On Campus”

Since Tinker, the Supreme Court has decided several other cases related to student free speech in schools, including Bethel School District v. Fraser, where the Court upheld the suspension of a student for using sexually explicit language during an assembly; Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, in which the Court ruled that a school could censor articles in a student newspaper on the topics of divorce and teen pregnancy if the censorship was “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns”; and Morse v. Frederick, in which the Court ruled that a school could prohibit a student from displaying a banner reading “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” at a school-sponsored event because it promoted illegal drug use.

The Material and Substantial Interference Test Outside the Schoolhouse

However, these cases all involved speech that occurred on school grounds or at school-sponsored events. The Mahanoy case is different because Levy’s speech occurred outside of school grounds and outside of school hours. The US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, which ruled in favor of Levy, applied the “material and substantial disruption” test from Tinker and found that Levy’s speech did not meet that standard.

Other US Circuit Courts have taken different approaches to the issue of regulating off-campus student speech. For example, the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in Wisniewski v. Board of Education of Weedsport Central School District that a school did not violate a middle school student’s First Amendment right when it disciplined him for sending an instant message from his home computer to a group of 15 friends. The message included an icon depicting the shooting of his English teacher, and the Court ruled that the speech was subject to Tinker because it posed a “foreseeable risk of substantial disruption within a school.” Similarly, the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled in Kowalski v. Berkeley County Schools that a school could discipline a student for off-campus speech if there is a sufficient nexus to the school’s pedagogical interests. In the case of Kowalski, a sufficient nexus was found when a high school student created a MySpace page titled S.A.S.H., an abbreviation for “Students Against Sluts Herpes,” that was used by Kowalski and classmates to humiliate and harass another student.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling for Levy

Ultimately, the Court ruled in favor of Levy and found that the school district had violated her First Amendment rights. Though schools have a legitimate interest in restricting off-campus speech when it can lead to bullying or harassment, Levy’s Snapchat speech did not rise to such a level. The Supreme Court additionally held that the test in Tinker was too broad to apply to off-campus speech. The justices also provided three factors that lessen the need for a school to restrict off-campus speech that does not lead to bullying or harassment:

- Parents are generally responsible for regulating a student’s off-campus speech.

- Off-campus speech regulations combined with a school’s on-campus speech regulations would mean that students could not exercise their First Amendment rights virtually anywhere.

- Schools themselves have an interest in protecting students’ First Amendment rights because schools are the “nurseries of democracy.”

However, the Court intentionally declined to further define the boundaries of when a school may regulate off-campus speech.

Conclusion

It is important to note that the circuit court decisions are not absolute and may be subject to further review and interpretation by higher courts. Additionally, the extent to which schools can regulate off-campus speech may depend on various factors, such as the nature and severity of the speech, its potential to disrupt the educational environment, and the student’s relationship to the school. As such, the issue of off-campus speech and school discipline remains a complex and evolving area of law. Reach out to member of our team to learn more.